Time travel to 18th c. Kasos

Part 1: How a French traveler unwillingly finds his way to Kasos and is welcomed by the locals

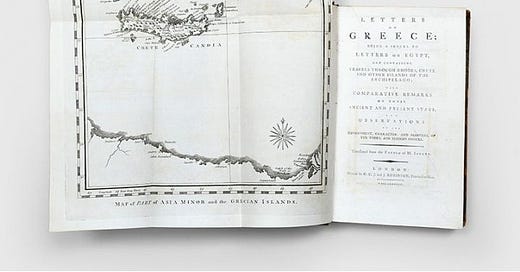

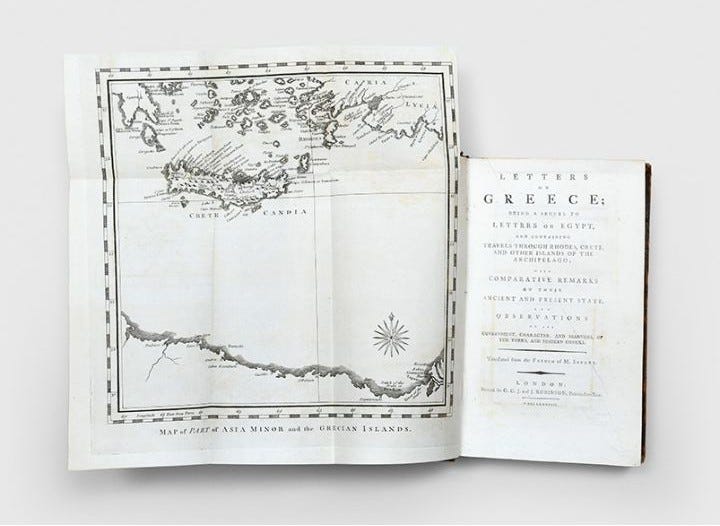

(Photo credit Peter Harrington rare books)

∞∞∞∞∞

When does a misfortune turn out to be good luck? A case in point is the arrival of Claude-Étienne Savary in Kasos sometime in 1779.

He writes:

“For two days we’d been trying to approach the coast of Crete, but our ship was cast about in the rough seas and buffeted by the wind. We could only look at Crete from afar, and eventually we resigned ourselves to landing at Kasos, all the while cursing our fate for the misfortune. But after staying among the Kasiots for eight days, I was pleased that the wind had carried on for so long.”

The French orientalist travelled to Egypt and the Greek-speaking lands in the late 1770s. His travel impressions were published in two volumes, Letters on Egypt and Letters on Greece. His Letters on Greece outline his journey from Alexandria, Egypt, as he passes through Castel Rosso (Kastellorizo), stays in Rhodes and Symi, and heads towards Candia (Crete). On the way there, the ship falls into adverse winds, which turned out to be his good luck and ours: his keen eye and pen recorded valuable glimpses of the Kasiots and their everyday life in Kasos that would otherwise be lost.

The letters are addressed to Madame Le Monnier. I have not been able to ascertain whether M.L.M. was a real person or simply a literary device; either way, the presence of the real or imagined addressee gives the writing freshness and immediacy. Letter 16 opens up a time-travel portal of two-and-a half centuries back to Ottoman Kasos.

Shall we step in?

∞∞∞∞∞

L E T T E R XVI

To M.L.M.

Casos

We must not always consider the obstacles we meet with at sea, Madam, as a misfortune, since sometimes we may derive more advantage from adverse winds than from prosperous ones. For two days we were within sight of the shores of Crete, without being able to land there. We kept looking at the verdant fields and beautiful views of that country, all the while grumbling against our fate and the wind, which was making us abandon them. Our anchoring in Casos seemed to me a misfortune. But since I got to know the inhabitants of that island, I have changed my opinion, so let the wind blow on: I don’t mind staying here a little longer.

[…]

The isle of Casos has suffered the common fate of the Archipelago. It is now subject to the Turks [Ottomans], but they dare not inhabit it, because it has no fort. The Turks are afraid of capture by the pirates of Malta, as has happened to them more than once at Antiparos, and other places without fortresses. This fear is a most fortunate circumstance for the inhabitants, who owe their tranquillity, happiness, and freedom to that fact alone.

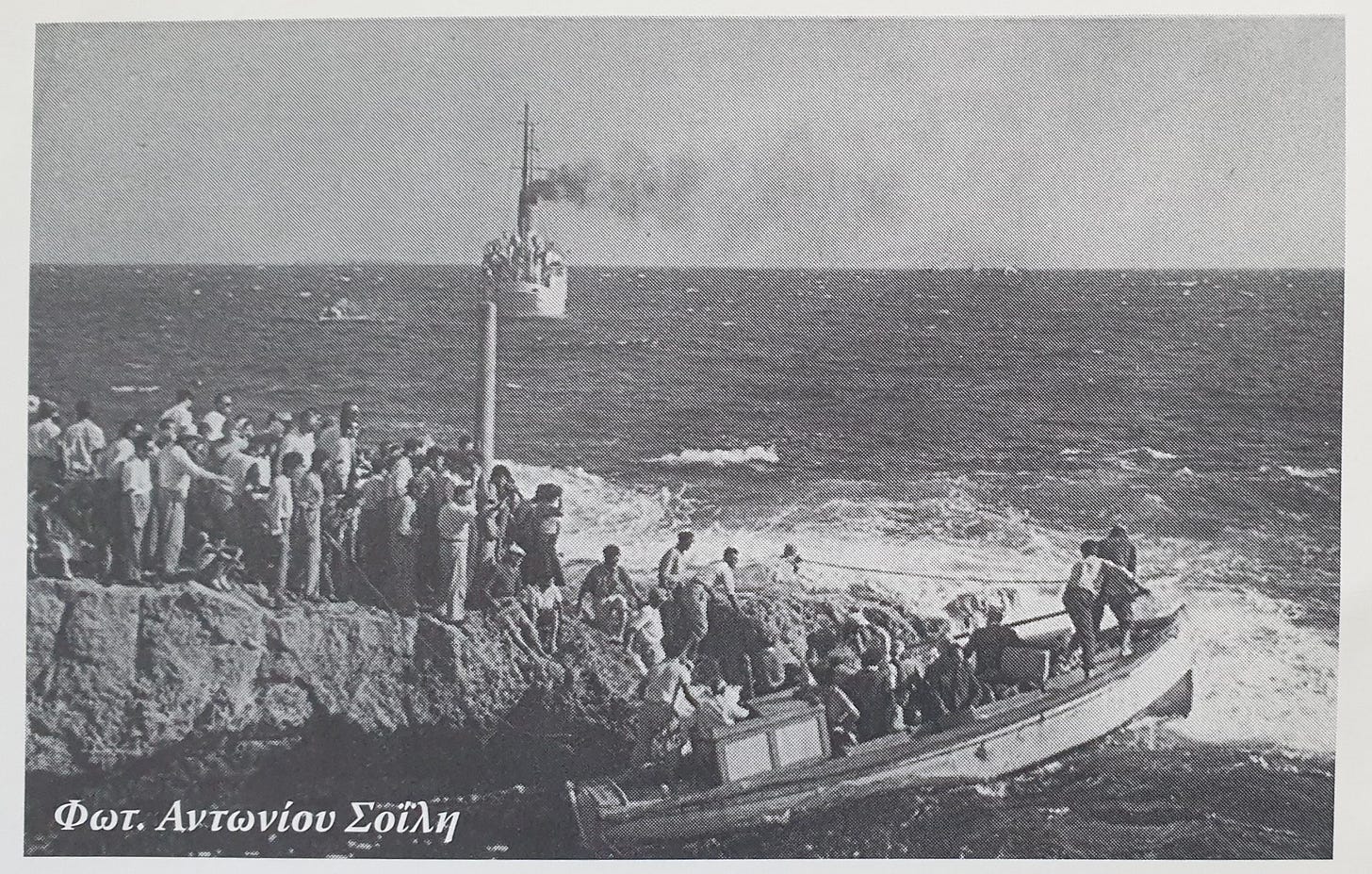

The day after we cast anchor, I was impatient to go on shore. The boat was launched, and we rowed towards the rocks which surrounded the island, but were at a loss where to land. Every part of the shore was defended by dangerous shoals, over which the foaming waves broke with great noise and violence. On whichever side we cast our eyes, Casos appeared inaccessible.

At length one of the inhabitants, seeing us in trouble, came down from the village, and waved his handkerchief to point out the place we should head towards. We reached the place, after coasting about a league along the island. The ground here becomes lower, and forms a valley, at the end of which a small basin has been dug for boats. The entrance is only twelve feet wide [3.6 m.], and very difficult to access, as it must be passed through exactly in the middle. If the boat touches the sides, formed by sharp rocks, it can be dashed to pieces. Apart from that, when we arrived before the entrance, a violent swell was ebbing out of it.

Bouka then, looking towards the north-west….(Photo credit Antonios Soilis - see notes at the end of the post)

…and now, looking eastwards (Photo credit Athena Mogadam)

The Casiot called one of his countrymen. They stood on either side of the small port and made a sign to us to pull strong. As soon as our boat had entered the dangerous pass, they guided it with long poles, to prevent it from striking against the rocks, and thus helped it into port. This passage alone [Bouka] is the only way to get on shore in the island. The inhabitants could widen, but they prefer leaving it as dangerous as it is, since in this way, they have little to fear from their enemies.

The Casiot, who had shown us the harbour, politely invited us to go up to the village, and we followed him with pleasure. I was dressed in the French style, with a sword, hat and every other accessory of my national dress. The news of the arrival of strangers soon spread, and the women and children came out of their houses and waited for us at the top of the hill. They showed a great deal of curiosity and examined us carefully. When we passed them, they all modestly cast down their eyes. Among the crowd, there were some very handsome. Several of them greeted us, wishing us a good day, with: “You're welcome!” and we answered them with the usual eastern expression: “May the day be happy for you and for your guests!”

The guide, who conducted us, was one of the principal inhabitants of the island. He asked me to step into his house and introduced me into a hall, which, though not luxurious, contained every necessary element of cleanliness and convenience. Around it was a sopha. He seated me on a raised bench [pangali], and placed himself below, while breakfast was prepared. Soon after, his wife and daughter appeared, with new-laid eggs, figs, and grapes. The girl blushed at sight of a stranger, whose dress and appearance must have looked extraordinary to her. Whilst we were breakfasting heartily, and my host was pouring me out some excellent wine in a large glass, most of the women of the village came to pay him a visit.

They greeted us and seated themselves without ceremony around the room. Curiosity had brought them there; they soon began to whisper to one another, and to make remarks on my French dress. Europeans rarely land in this solitary island, and the inhabitants, useed to seeing nothing but shaven heads, wrapped around with shawls, long robes fastened with sashes, and long beards, could only gaze with astonishment at a foreigner with long plaited hair, without even a moustache, wearing a cocked hat and a short coat, that came down no lower than his knees.

(Photo credit Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, retrieved from Pinterest)

They seemed quite impressed by the contrast. A half smile, which was sometimes seen on their faces, was probably a sign they were making funny comments on how strange my outfit was; as for me, I was equally amused with them. My attention was especially drawn to two young females, who would be considered beautiful, even in Paris.

(to be continued in the next post)

∞∞∞∞∞

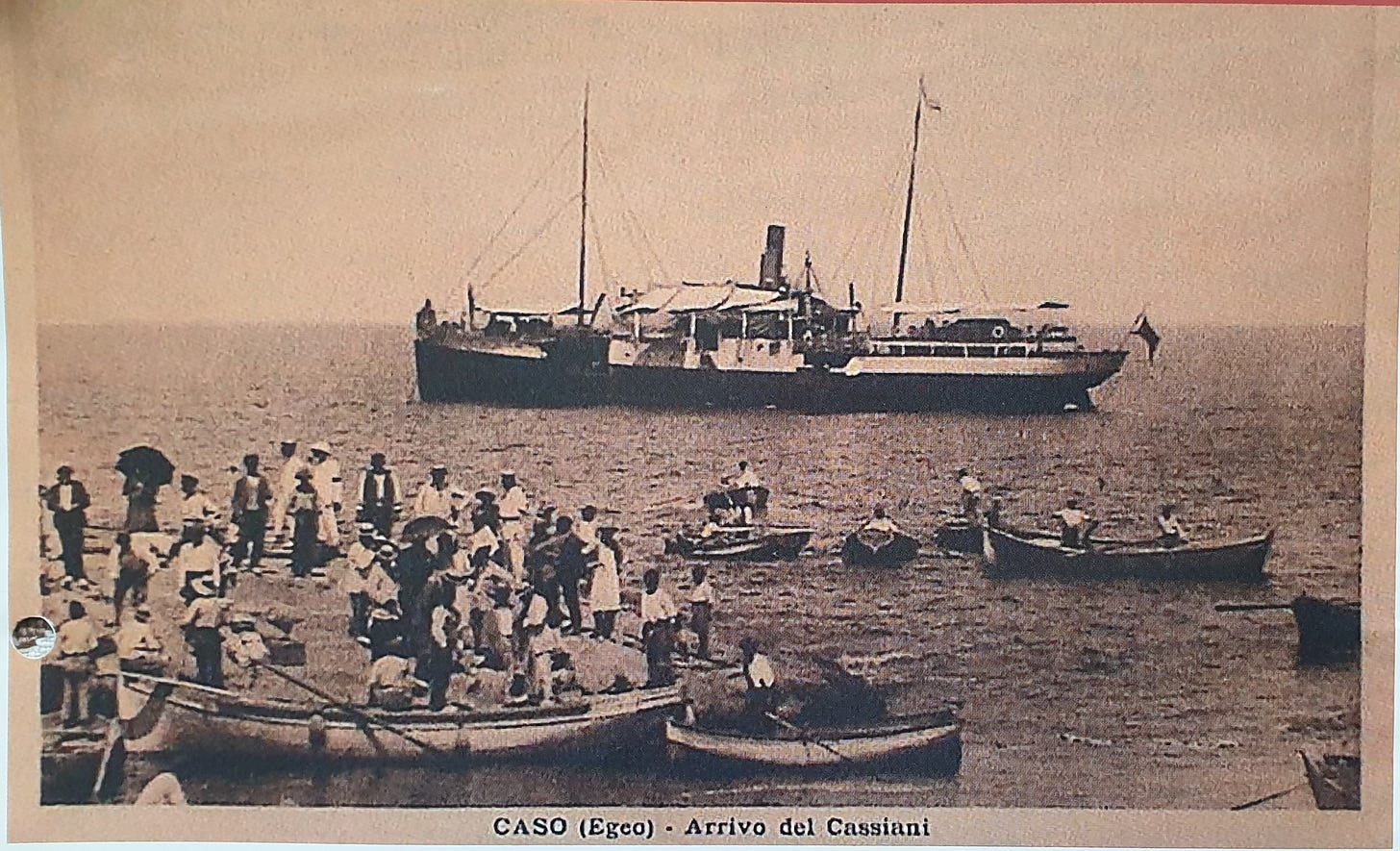

The way of landing in Kasos remained the same until the mid 1960s when the port of Emboreios was completed. But even then, when the sea was rough, the ship would dock by the desert island of Makra, north of Bouka, and boats would ferry passengers and cargo back and forth.

If you’re an old and lucky enough Kassiot, this description would sound familiar. If you’re younger, have you heard such stories from parents and grandparents? Share them below!

(Photo: postcard from the Italian occupation 1912 - 1947)

Photo credits Antonios Soilis - also see notes at the end of the post)

Fascinating! "Let the wind blow on: I don’t mind staying here a little longer"! How I feel about staying here with your Kasos Chronicles!